Concert Overview

April 22nd, 7:30 pm at Capitol Theater

The program:

- JANÁČEK | Suite for Strings

- CHERUBINI | Symphony in D major [intermission]

- BEETHOVEN | Piano Concerto No. 5, Emperor

Suite for Strings

Leoš Janáček, along with Dvořák and Bedřich Smetana we’ve covered in class, is considered one of the best Czech composers. He is a diligent worker, although he did not become famous until he was fiftyish. By the time he was in his 70s, he was well-sought after and someone asked him if he had any unshown work, he searched through his archives and took out this work which he composed fifty years ago at the age of 24. At that time, a composer was considered a serious one only if he/she had composed a suite for strings, so he did, although the piece went rather unnoticed.

Because of the wide range of moods it tries to depict, this piece has a relatively equal share of play for each part of the strings. For example, in movement V, the cello steals the spotlight and performs an extremely calm, sad, and legato melody. The mood change is also suggested by the tempo of each movement: besides the first (Moderato) and the last movement (Andante), the tempo goes from Adagio to Andante, and finally peaks at Presto, then it recedes to Adagio, where the solo cello plays. The Presto movement is like the lively 3rd movement of Tchaikovsky’s 6th Symphony, whereas the Adagio movement is a sharp contrast in terms of tempo and mood that is comparable to the 4th movement of the 6th Symphony. Moreover, this piece has more symmetry in addition to the symmetric tempo. The melody played in the first movement, the intro, is “recapped” in the last movement as if Janáček wants to close the loop.

My favorite movement is the last movement. It sounds like the orchestra is recovered from the sadness of the 5th movement. There is one section where it sounds like the dialogue between the lower strings and the upper strings: the lower strings first pose a daunting question (a four-note downward tune), the upper strings respond by repeating the question with a lower dynamic (imitating) as if the person being asked is unsure and unconfident. Then the upper strings press on and repeat asking the same question again while raising the volume, but this time the upper strings vary the question a bit and continue playing without the interruption of the lower strings.

Symphony in D Major

Although his works besides opera are not among the most-played repertoire now, Luigi Cherubini was regarded by Beethoven as the greatest of his contemporaries (not sure if Beethoven included himself). In particular, this work is one of the few existed orchestra works between Mozart and Haydn and the array of romantic composers starting from Felix Mendelssohn, besides the Beethoven repertoire. Therefore, he could be seen as a transitional figure between the classical era and the romantic era. While he was in charge of the Conservatoire de Paris, Cherubini mentored Rossini, who really admired his opera work, Chopin, and Berlioz who described Cherubini as a crotchety pedant after refusing to leave when he crossed the “female” door without knowing he shouldn’t be because of the rule made by Cherubini and then being chased by Cherubini and his assistants around the library’s tables.

It is hard to believe that Cherubini is the type of person portrayed by Berlioz and by Adolphe Adam who wrote “some maintain his temper was very even, because he was always angry.” On the contrary, this symphony is really elegant, lighthearted, and beautiful: it mainly uses strings and woodwinds, and only rarely some timpani can be heard. It is in sharp contrast to Beethoven’s symphonies. When Cherubini was commissioned in 1815 to compose this work, the first 8 symphonies of Beethoven had been published and must be known to him, but he chose not to rely on brass and percussion to maintain the lightness. Since Cherubini only uses strings and woodwinds in this work, he often engages the two parts in conversations and imitations to have a sense of playfulness. A prominent example could be seen in the 3rd movement, a Minuet, where a string melody is answered by a light one-note played by the flute. I highly doubt that there is any “heavy” element in this work that makes people ponder rather than slightly raises the corners of people’s mouths. The first and the 3rd movement are maybe the most relaxed movements I have heard, something for people at that time to consider after listening to Beethoven’s 5th Symphony.

Piano Concerto No. 5, the Emperor

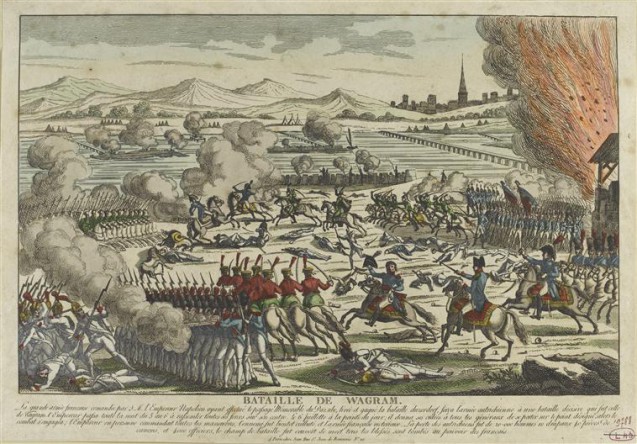

Speaking of Beethoven, here he is, the emperor. He is arguably the emperor of classical music, maybe of music in general, although he hates the notion of “emperor”, which is a misnomer of this piano concerto, which was dedicated to his patron Archduke Rudolf. However, he was by no means the emperor of his life around the time he composed this concerto, or most of the time in his life, when Vienna, his city, was under siege by Napoleon’s armies and Rudolf left him in a cellar.

However, “the Emperor” was composed during Beethoven’s heroic period, and the opening three sonorous chords played by the tutti seem to confirm the sublimeness, leading to an unusually early cadenza. The strings and percussions continue the expression of affirmative and heroic emotions in the orchestra’s exposition and mostly throughout the first movement. But, as if he wanted to demonstrate the environment around him, as he put it “nothing but drums, cannons, men, misery of all sorts”, and to express his desire for inner peace, we also can hear some soft, serene melodies played by woodwinds and the soloist. The contrast in emotions is powerful, and more importantly, the transition between heroic and serene is super smooth: he uses woodwinds as the bridge between the affirmative strings and the piano, then the piano takes the woodwinds’ turn and plays some affirmative chords with higher dynamic, after that it decrescendos and finally transitions to one of the softest and the most beautiful melodies I’ve heard. The woodwinds or the horns then pick up the soloist by accompanying his remaining chords and send us back to the heroic theme played by the strings. Therefore, the soloist has to show contrasting emotions with a convincing transition.

The second movement has a more consistent mood, as the piano and the tutti are either played together or extending the expressions just played by the other. I feel like some melodies in this movement have appeared in many war movies at the part when the war is over and people come back to their destructed home. If the directors of those films are understanding the movement “correctly”, then the subsequent 3rd movement (like Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, the last movement begins without pause) is for sure a lively and happily welcoming-back party for Rudolf. In addition to the relatively shorter time of the last two movements compared to the 20ish minutes of the first movement, another reason for Beethoven to coalesce the two movements is to maybe offer a contrast in mood. As John O’Conor, the soloist, said: “There are few people who know that Beethoven has a sense of humor. In the 2nd movement, he despairs in the cellar, and soon he portrays peasants dancing as if they are busy preparing for Rudolf’s return. "