Concert Overview

March 13th, 2:30 pm at Overture Center

The concert’s program consists of three pieces: it starts with Rachmaninoff’s Isle of the Dead, then it continues with Kodály’s Suite from the opera Háry János, and it ends with Ludwig Beethoven’s violin concerto Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 61 after the intermission.

Isle of the Dead

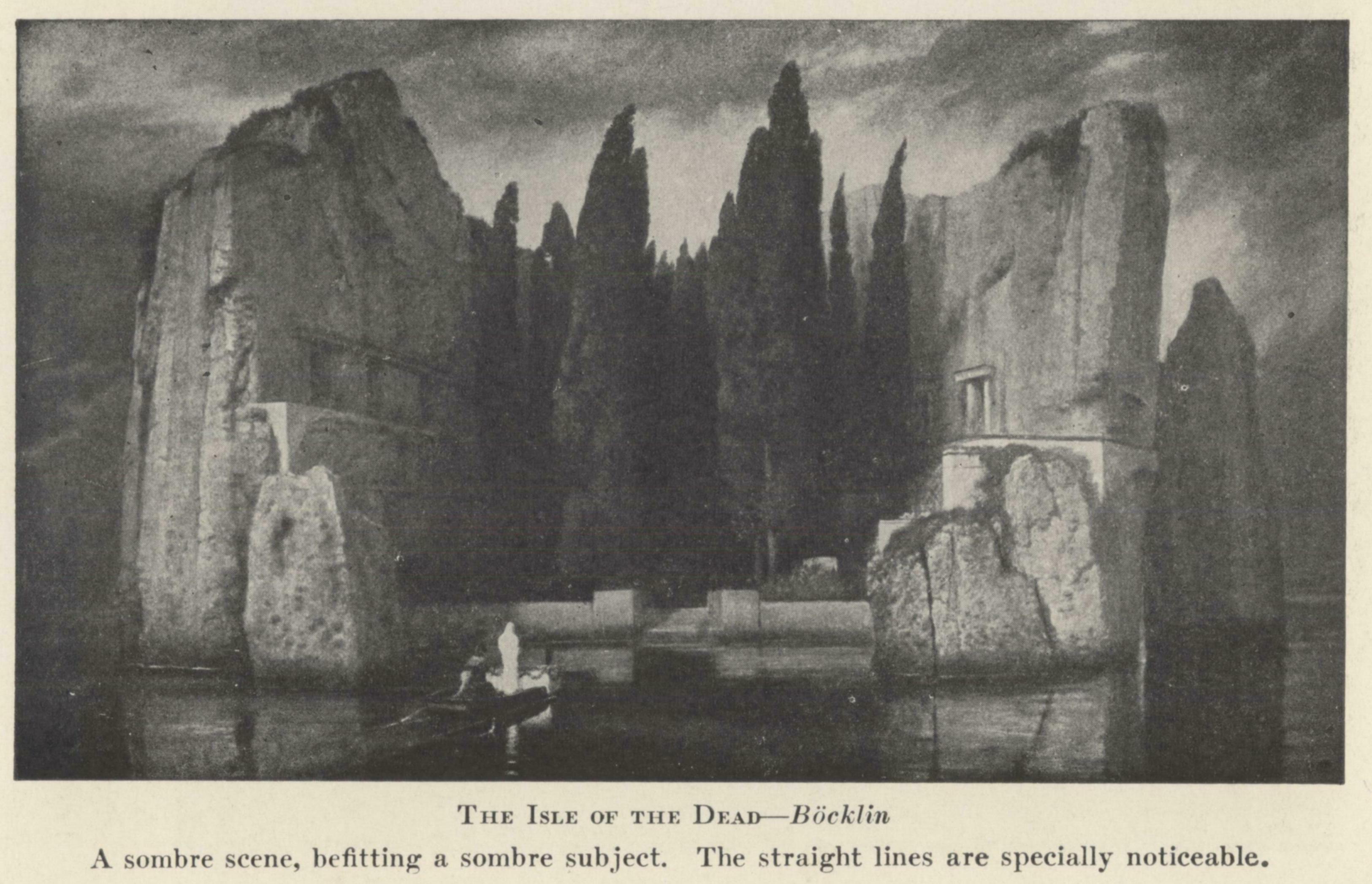

If Beethoven’s concerto is the main course that features the highly anticipated performance from the violin virtuoso Gil Shaham, then Rachmaninoff’s symphonic poem Isle of the Dead is the direct opposite to the relaxing apéritif that should bring us a trifle tipsiness. Instead, it is solemn, sober, and requires the audience’s full energy to feel the approach of death and then decide to fight or accept it. The opening 5/8 asymmetrical meter portrays Charon(boatman of the underworld) rowing the boat on the Styx River with thick and oily water towards the island of the dead – this piece is inspired by Böcklin’s painting “Isle of the Dead” which portrays the same event. The 2 strokes on the left and 3 on the right (later the reverse) are gentle, rhythmic, and hypnotic, intending to soothe the passenger and bringing the near-dead to sleep. Also, Rachmaninoff used this unusual meter to incorporate some Russian elements into this piece, as Russian folk songs often use the 5 meter instead of the more “regular” ones. As the boat is going forward, the seemingly incessant rowing tune represented by lower strings and brass disappears and is replaced by the gentle slow upper string and woodwind sound [5:27], as if the soul is awakened now as the boat is approaching the island. This passage expresses the reluctance to part with life; [7:07] as the boat keeps moving the emotion is evolved into uneasiness as if the soul now can see the brink of the island. Just as to confirm that, the rowing tune starts again since there is no stop for Charon [8:56]. The rowing tune builds up tension as if the boat is pulling onto the shore and the brass instruments increase their dynamics that result in the climax, the signal of the boat crashing onto the docking area [9:55]. The first section concludes when the brass recedes and the sound of the gentle yet weak soul represented by strings and woodwinds appears and gradually disappears.

The middle section starts with dour brass [11:11], indicating the “welcoming” message from the island. Then it transitions to an extremely beautiful melody played by the strings [11:40]. This passage portrays the longing for the dead from the alive. In one version of the painting, the version that inspired this piece, Böcklin was commissioned by Marie Berna to add the female figure and the coffin to the painting, to express Marie’s longing for her dead husband. I think Rachmaninoff fuses this longing into this fragment of the piece. However, they are not allowed a lengthy farewell (Charon is busy). The upper string melody is later joined by bass string and brass, and the tempo keeps increasing (tension!), and finally is consumed by brass and three clashes of cymbals [14:42]. The near-dead is now taken away. From [15:06] to [15:51], the repeated “long-short-short-short-long” rhythmic pattern is played by brass, increasing in pitch and dynamic, and imitated by upper strings, as if the personnel (played by brass) at the island is “accompanying” the dead (played by upper strings) to climb up the stairs, and as they go higher and higher, the pitch and dynamic become higher and higher. [15:52]The tension continues to build as the upper strings change to a different 4-note melody that sounds like screaming as if the near-dead realizes what is imminent when he looks down the hill. He/she wants to break free from the “accompanying” personnel, but it is impossible as the string melody is tightly gripped by the accompanying brass and yet again conquered, vanquished, consumed by the brass and cymbals [16:17]. The brass triumphs, and laughs rather evilly (represented by the 4 notes) [16:30].

Finally, the near-dead achieves death when the final section begins with Dies Irae [16:37]. The 4-note melody is repeated again and again in woodwinds just like the death is hypnotizing the dead. [17:18]Suddenly, the fast-paced 4-note Dies Irae played by the shiveringly tremoloed string is fast approaching to give the dead the final blow, and then it resolves to a peaceful woodwind melody to relieve the struggle of the dead. After a brief orchestral mourning of the dead, the 5/8 rowing tune reappears [19:10] – Charon is setting out for another duty, another business in his perspective. The appearance and the return of the tune embody the cycle of the leave and return to the island.

Charon is the action (he rows people to death) and the concept/subject itself. The requirement of becoming a concept is objectivity. For example, “love” in “Alice loves Bob” is not a concept but an action, but “love” without Alice and Bob is a concept. His objectivity, emotionlessness, and fairness make him the perfect symbol of death. Maybe in his early career, he wants to know, but over time, he has become the concept itself, senseless and careless of who is on the boat. To do that, he has to immerse himself into the cycle and repeat it many times so that he could forget which iteration of the cycle he is currently in (to get a feeling of what it likes or what takes to be Charon, you could play the Isle of the Island in loop).

Note and some final thoughts

Like many pieces composed during the Romantic period, Isle of the Dead is program music. Moreover, it is a symphonic poem that uses a single continuous movement to illustrate an idea. The narrative is not as explicit as that of Kodály’s Suite from the opera Háry János, but it can be to some extent deduced, interpreted, and reconstructed, under the title of this piece and Böcklin’s painting. This piece tries to explore the ultimate unknown of the human being, namely, the passage between life and death. My attempt at understanding this piece starts with the emotion evoked by the melody, variation, repetition, or progressions of the tone colors, dynamics, pace, and pitch, then tries to fill in the imagined narrative that evokes the same emotion. Therefore, it is an attempt of me to construct a mapping from the orchestral effort to the narrative (just as if it is narrated in a poem).

The timeline is constructed under a recording from the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra.

Therefore, the exact timestamps vary by different recordings. Also, like there exist different versions of recordings, interpretation of the piece varies. Similarly, this piece is Rachmaninoff’s interpretation of Böcklin’s painting. Although this piece was inspired by the painting, it is self-contained and it represents his understanding of the subject, death. Equivalently, this piece inspired me to ponder over this subject. Moreover, just as Rachmaninoff was “haunted” by death – he composed several pieces that contain the “Dies Irae” chant over the years, I am sure my interpretation will change as I relisten to this piece in the future. This neverending and eternal momentum that inspires changes is one of the best qualities of the best arts, which makes it timeless.

Suite from the opera Háry János

As the name suggests, it is the orchestra version of the opera Háry János, so it is a highly “programmed” set of pieces that follow closely with the plot and the emotion of the characters. The story is of an Austrian peasant and veteran who sits in the village inn telling fantastic tales of him winning the heart of Marie Louise, the wife of Napoleon, and singlehandedly defeating Napolean and his armies.

I would imagine that anyone who has watched the opera or know the story could understand and fill in the plot while listening to this suite. For example, in the fourth movement, the story goes that Napoleon orders the troops to attack, but eventually kneels down and begs for mercy and his wife’s heart. All these can be heard through the solo saxophone that personifies Napoleon. The soloist sat through the first 3 movements (with the mask on), but in the 4th movement, he started playing a melancholy tune, signaling Napolean’s remorse over the loss of his wife’s heart to the antagonist. Another very Hungarian and narrative-related sound is called an orchestral “musical sneeze”, which starts the suite off, as best explained in Kodály’s own words: “According to Hungarian superstition, if a statement is followed by a sneeze of one of the hearers, it is regarded as confirmation of its truth.”

This suite also makes use of one of the Hungarian’s traditional instruments, the cimbalom, which uses a pair of hammers to strike the strings to make sounds. The tone color is very unique. In the 3rd movement, the tones played by the cimbalom remind me of Guzheng, a Chinese plucked string instrument. In the intermezzo movement, my favorite movement, which is light and mellow since it is the intermission between the victory over Napolean and the final commendation by the emperor in his palace, its tone color is close to a harpsichord. I am amazed that in Madison Symphony Orchestra they have that instrument and have someone who knows how to play it.

We know that Háry János is a bragger, but somehow we do not feel like laughing at him but sympathizing with him. It again can be best summed up in Kodály’s own words: “Every Hungarian is a dreamer. He flees from the sad reality of the centuries…into the world of illusions. Yet Háry János’s boasting is more than a dream: it is also poetry. The authors of heroic tales are themselves no heroes, but they are the spiritual kin of heroes. Háry János may never have done the deeds he talks about, but the potential is always there. János is a primitive poet, and what he has to say he concentrates on a single hero: himself. After we have listened to the heroic feats he has dreamed up, it is tragically symbolic that we see him in a grubby village inn. He appears happy in his poverty: a king in the kingdom of his dreams.” We can hear the underlying melancholy in the intermezzo, to some degree disguised by the happiness, because we know it is not true happiness and the music wants to covertly show us that as well. Another more explicit representation of the sadness is in the 3rd movement, the “Song”, a slow, melancholy movement that is about Háry and his fiancée Orsze’s longing for home and their wish for a little cottage when they return. We no longer know whether this is still bragging or reality.

Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 61

Contrary to the pieces played before the intermission, the “main course” is not program music, so there exist infinitely many possibilities. For now, it still requires more listening to come up with my analysis. I’ve heard one soloist say that while playing this concerto he feels like he is a little bird crossing the vast sea that is portrayed by the orchestra. This interpretation indeed reveals one characteristic of this piece – the equality and the balance between the soloist and the remaining orchestra, which is shown for example in the first part of the first movement, where the orchestra plays the main melody and the soloist sometimes accompanies the orchestra the other time plays his notes in juxtaposition to the main melody. This balance was uncommon in Beethoven’s time when audiences and soloists expected to see/hear and play some flamboyant showmanship. It is not surprising that Franz Clement, to whom this piece was dedicated, did not prepare at all for the premier, inserted his sonatas while playing, and onetime during the play held the violin upside-down, and the reviews were not favorable. I am not sure how this act related to the subsequent facts such as Beethoven only composed one violin concerto (another “tradition” set forth by Beethoven followed by Tchaikovsky and Brahms, etc.) and he later explicitly wrote out notes for cadenzas in concertos (e.g. Beethoven’s 5th piano concerto).

But this is not to say that the virtuosity of the soloist is not manifested at all. Although I am not familiar with the violin techniques and therefore cannot assess the difficulty of playing solo, there are a lot of high trills but none of them played by Gil Shaman, the soloist, is harsh. His smiles when he was not playing convey the utter happiness of the “bird”.